"In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense."

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution affords criminal defendants seven discrete personal liberties: (1) the right to a Speedy Trial; (2) the right to a public trial; (3) the right to an impartial jury; (4) the right to be informed of pending charges (5) the right to confront and to cross-examine adverse witnesses; (6) the right to compel favorable witnesses to testify at a trial through the subpoena power of the judiciary and (7) the right to legal counsel.

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution affords criminal defendants seven discrete personal liberties: (1) the right to a Speedy Trial; (2) the right to a public trial; (3) the right to an impartial jury; (4) the right to be informed of pending charges (5) the right to confront and to cross-examine adverse witnesses; (6) the right to compel favorable witnesses to testify at a trial through the subpoena power of the judiciary and (7) the right to legal counsel.

Speedy Trial

The right to a speedy trial traces its roots to the twelfth-century England, when the Assize of Clarendon declared that justice must be provided to robbers, murders, and thieves "speedily enough." This Speedy Trial Clause was designed by the Founding Fathers to prevent defendants from languishing in jain for an indefinite period before trial to minimize the time in which a defendant's life is disrupted and burdened by the anxiety and scrutiny accompanying public criminal proceedings, and o reduce the chances that a prolonged delay before trial will impair the ability of the accused to prepare a defense.

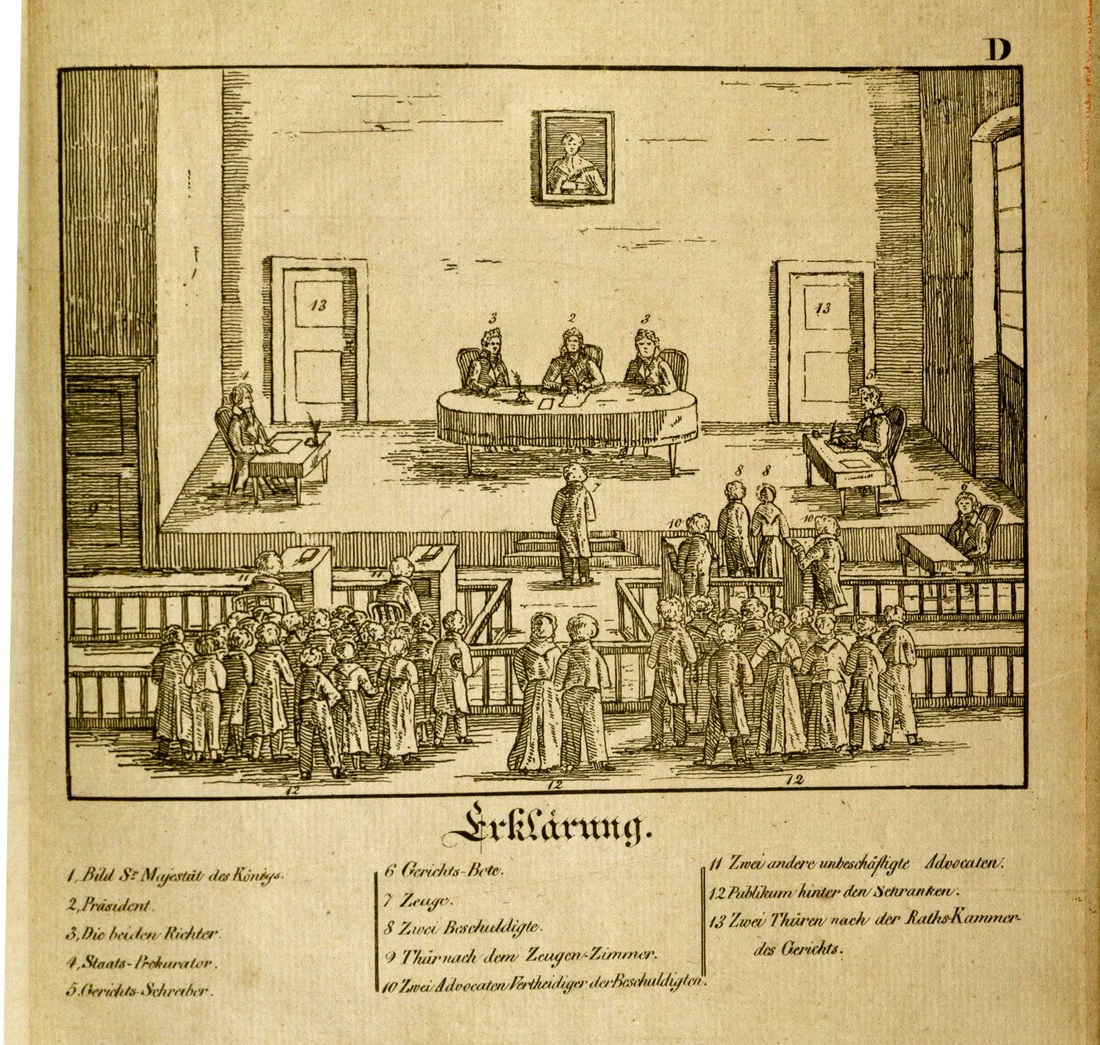

Public Trial

The right to a public trial is another ancient liberty that Americans have inherited from Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence. During the seventeenth century, when the English Court of Oyer and Terminer attempted to exclude members of the public from a criminal proceeding that the Crown had deemed to be sensitive, defendant John Lilburn successfully argued that immemorial usage and British Common Law entitled him to a trial in open court where spectators are admitted. The Founding Fathers believed that public criminal proceedings would operate as a check against malevolent prosecutions, corrupt or malleable judges, and perjurious witnesses. The public nature of criminal proceedings also aids the fact-finding mission of the judiciary by encouraging citizens to come forward with relevant information, whether inculpatory or exculpatory.

The Right to Trial by an Impartial Jury

In both England and the American colonies, the Crown retained the prerogative to interfere with jury deliberations and to overturn verdicts that embarrassed, harmed, or otherwise challenged the authority of the royal government. Finding such interference unjust, the Founding Fathers created a constitutional right to trial by an impartial jury. This Sixth Amendment right, which can be traced back to the Magna Charta in 1215, does not apply to juvenile delinquency proceedings (McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, 403 U.S. 528, 91 S. Ct. 1976, 29 L. Ed. 2d 647 [1971]), or to petty criminal offenses, which consist of crimes punishable by imprisonment of six months or less.

Notice of Pending Criminal Charges

The Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation against them. Courts have interpreted this provision to have two elements. First, defendants must receive notice of any criminal accusations that the government has lodged against them through an indictment, information, complaint, or other formal charge. Second, defendants may not be tried, convicted, or sentenced for a crime that materially varies from the crime set forth in the formal charge. If a defendant suffers prejudice or injury, such as a conviction, from a material variance between the formal charge and the proof offered at trial, the court will vacate the verdict and sentence.

Confrontation of Adverse Witnesses

The Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to be confronted by witnesses who offer testimony or evidence against them. The Confrontation Clause has two prongs. The first prong assures defendants the right to be present during all critical stages of trial, allowing them to hear the evidence offered by the prosecution, to consult with their attorneys, and otherwise to participate in their defense. However, the Sixth Amendment permits courts to remove defendants who are disorderly, disrespectful, and abusive. If an unruly defendant insists on remaining in the courtroom, the Sixth Amendment authorizes courts to take appropriate measures to restrain him. In some instances, courts have shackled and gagged recalcitrant defendants in the presence of the jury. In other instances, defiant defendants have been removed from court and forced to watch the remainder of trial from a prison cell, through closed-circuit television.

Compulsory Process for Favorable Witnesses

As a corollary to the right of confrontation, the Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to use the compulsory process of the judiciary to subpoena witnesses who could provide exculpatory testimony or who have other information that is favorable to the defense. The Sixth Amendment guarantees this right even if an indigent defendant cannot afford to pay the expenses that accompany the use of judicial resources to subpoena a witness (United States v. Webster, 750 F.2d 307 [5th Cir. 1984]). Courts may not take actions to undermine the testimony of a witness who has been subpoenaed by the defense. For example, a trial judge who discourages a witness from testifying by issuing unnecessarily stern warnings against perjury has violated the precepts of the Sixth Amendment.

Right to Counsel

Because of the law's complexity and the often substantial deprivations that a criminal conviction can produce, the Sixth Amendment provides criminal defendants with a Right to Counsel. A defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel attaches when the government initiates adversarial criminal proceedings, whether by way of formal charge, Preliminary Hearing, indictment, information, or Arraignment (United States v. Larkin, 978 F.2d 964 [7th Cir. 1992]). Unlike the right to a speedy trial, this Sixth Amendment right does not arise at the moment of arrest unless the government has already filed formal charges (Kirby v. Illinois, 406 U.S. 682, 92 S. Ct. 1877, 32 L. Ed. 2d 411 [1972]). However, defendants may assert a Fifth Amendment right to consult with an attorney during Custodial Interrogation by the police, even though no formal charges have been brought and no arrest has been made