The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

The Tenth Amendment, which makes explicit the idea that the federal government is limited only to the powers granted in the Constitution, has been declared to be truism by the Supreme Court. In United States v. Sprague (1931) the Supreme Court asserted that the amendment "added nothing to the [Constitution] as originally ratified."

States and local governments have occasionally attempted to assert exemption from various federal regulations, especially in the areas of labor and environmental controls, using the Tenth Amendment as a basis for their claim. An often-repeated quote, from United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100, 124 (1941), reads as follows:

The amendment states but a truism that all is retained which has not been surrendered. There is nothing in the history of its adoption to suggest that it was more than declaratory of the relationship between the national and state governments as it had been established by the Constitution before the amendment or that its purpose was other than to allay fears that the new national government might seek to exercise powers not granted, and that the states might not be able to exercise fully their reserved powers.

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

The Ninth Amendment has generally been regarded by the courts as negating any expansion of governmental power on account of the enumeration of rights in the Constitution, but the Amendment has not been regarded as further limiting governmental power. The U.S. Supreme Court explained this, in U.S. Public Workers v. Mitchell 330 U.S. 75 (1947): "If granted power is found, necessarily the objection of invasion of those rights, reserved by the Ninth and Tenth Amendments, must fail."

It is important, when discussing the history of the Bill of Rights, to realize the Supreme Court held in Barron v. Baltimore (1833) that it was enforceable by the federal courts only against the federal government, and not against the states. Thus, the Ninth Amendment originally applied only to the federal government, which is a government of enumerated powers.

Some jurists have asserted that the Ninth Amendment is relevant to interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Arthur Goldberg (joined by Chief Justice Earl Warren and Justice William Brennan) expressed this view in a concurring opinion in the case of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965):

The Framers did not intend that the first eight amendments be construed to exhaust the basic and fundamental rights.... I do not mean to imply that the .... Ninth Amendment constitutes an independent source of rights protected from infringement by either the States or the Federal Government....While the Ninth Amendment - and indeed the entire Bill of Rights - originally concerned restrictions upon federal power, the subsequently enacted Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the States as well from abridging fundamental personal liberties. And, the Ninth Amendment, in indicating that not all such liberties are specifically mentioned in the first eight amendments, is surely relevant in showing the existence of other fundamental personal rights, now protected from state, as well as federal, infringement. In sum, the Ninth Amendment simply lends strong support to the view that the "liberty" protected by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments from infringement by the Federal Government or the States is not restricted to rights specifically mentioned in the first eight amendments. Cf. United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 94-95.

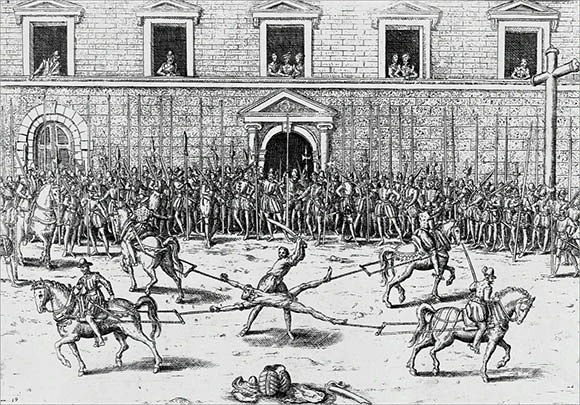

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted. The Eighth Amendment was adopted, as part of the Bill of Rights, in 1791. It is almost identical to a provision in the English Bill of Rights of 1689, in which Parliament declared, "as their ancestors in like cases have usually done that excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted." The provision was largely inspired by the case in England of Titus Oates who, after the ascension of King James II in 1685, was tried for multiple acts of perjury which had caused many executions of people whom Oates had wrongly accused. Oates was sentenced to imprisonment including an annual ordeal of being taken out for two days pillory plus one day of whipping while tied to a moving cart. The Oates case eventually became a topic of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. The punishment of Oates involved ordinary penalties collectively imposed in an excessive and unprecedented manner. The reason Oates did not receive the death penalty (unlike those whom he had falsely accused) may be because such a punishment would have deterred even honest witnesses from testifying in later cases

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Prior to the Glorious Revolution of 1688, English judges were seen as "lions under the throne",,servile creatures of the King. As English judges held their sinecures at the pleasure of the King, they were sometimes biased in favor of the King and did not always make their rulings in an impartial manner. As such, the jury was an essential countervailing force against tyranny, insofar as the jury had every right to ignore a judge's instructions, thwarting even the will of the King. William Blackstone wrote that it was "the most transcendent privilege which any subject can enjoy, or wish for, that he cannot be affected either in his property, his liberty, or his person, but by the unanimous consent of twelve of his neighbors and equals.

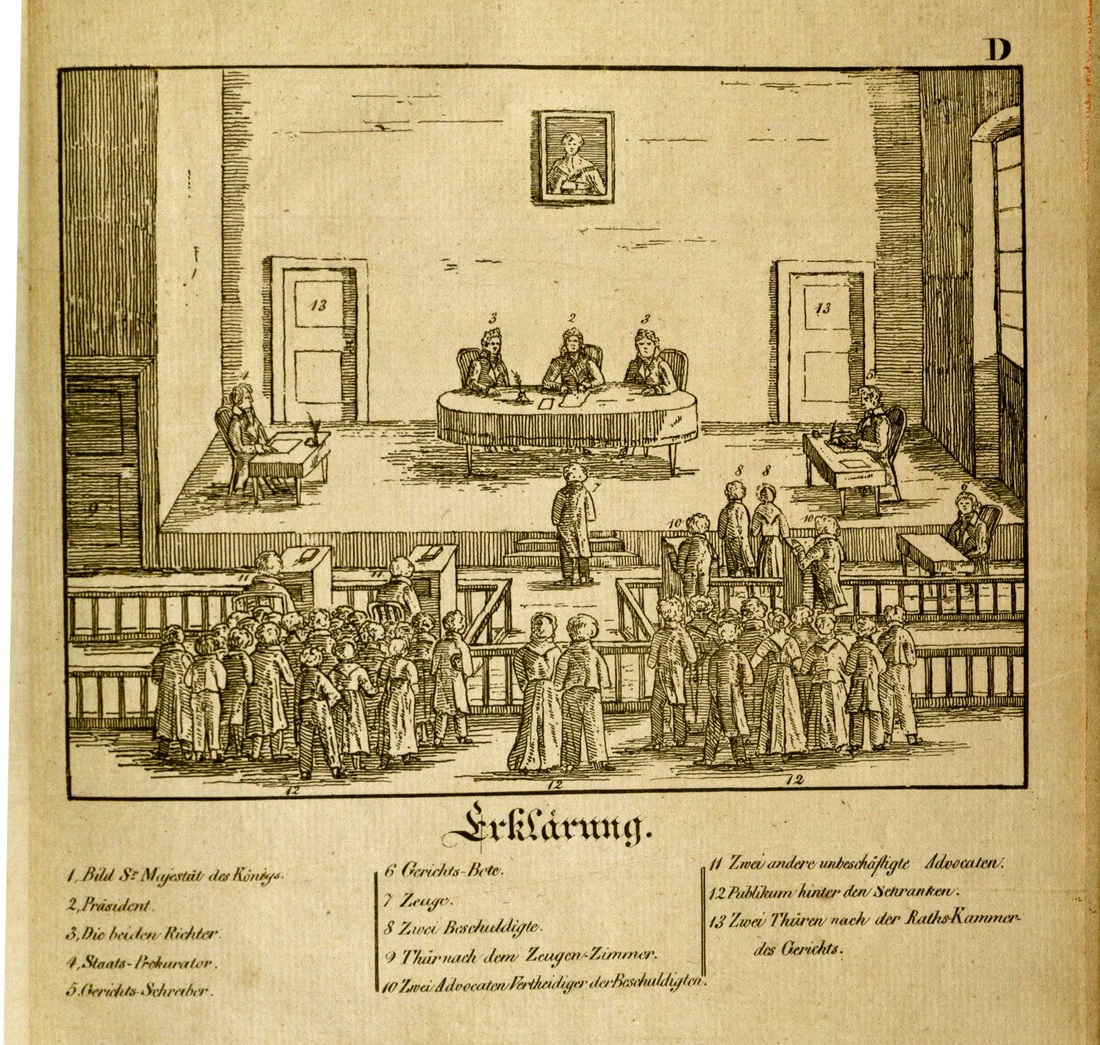

"In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense."

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution affords criminal defendants seven discrete personal liberties: (1) the right to a Speedy Trial; (2) the right to a public trial; (3) the right to an impartial jury; (4) the right to be informed of pending charges (5) the right to confront and to cross-examine adverse witnesses; (6) the right to compel favorable witnesses to testify at a trial through the subpoena power of the judiciary and (7) the right to legal counsel.

Speedy Trial The right to a speedy trial traces its roots to the twelfth-century England, when the Assize of Clarendon declared that justice must be provided to robbers, murders, and thieves "speedily enough." This Speedy Trial Clause was designed by the Founding Fathers to prevent defendants from languishing in jain for an indefinite period before trial to minimize the time in which a defendant's life is disrupted and burdened by the anxiety and scrutiny accompanying public criminal proceedings, and o reduce the chances that a prolonged delay before trial will impair the ability of the accused to prepare a defense. Public Trial The right to a public trial is another ancient liberty that Americans have inherited from Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence. During the seventeenth century, when the English Court of Oyer and Terminer attempted to exclude members of the public from a criminal proceeding that the Crown had deemed to be sensitive, defendant John Lilburn successfully argued that immemorial usage and British Common Law entitled him to a trial in open court where spectators are admitted. The Founding Fathers believed that public criminal proceedings would operate as a check against malevolent prosecutions, corrupt or malleable judges, and perjurious witnesses. The public nature of criminal proceedings also aids the fact-finding mission of the judiciary by encouraging citizens to come forward with relevant information, whether inculpatory or exculpatory.

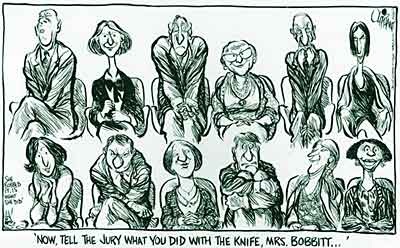

The Right to Trial by an Impartial Jury In both England and the American colonies, the Crown retained the prerogative to interfere with jury deliberations and to overturn verdicts that embarrassed, harmed, or otherwise challenged the authority of the royal government. Finding such interference unjust, the Founding Fathers created a constitutional right to trial by an impartial jury. This Sixth Amendment right, which can be traced back to the Magna Charta in 1215, does not apply to juvenile delinquency proceedings (McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, 403 U.S. 528, 91 S. Ct. 1976, 29 L. Ed. 2d 647 [1971]), or to petty criminal offenses, which consist of crimes punishable by imprisonment of six months or less.

Notice of Pending Criminal Charges The Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation against them. Courts have interpreted this provision to have two elements. First, defendants must receive notice of any criminal accusations that the government has lodged against them through an indictment, information, complaint, or other formal charge. Second, defendants may not be tried, convicted, or sentenced for a crime that materially varies from the crime set forth in the formal charge. If a defendant suffers prejudice or injury, such as a conviction, from a material variance between the formal charge and the proof offered at trial, the court will vacate the verdict and sentence.

Confrontation of Adverse Witnesses The Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to be confronted by witnesses who offer testimony or evidence against them. The Confrontation Clause has two prongs. The first prong assures defendants the right to be present during all critical stages of trial, allowing them to hear the evidence offered by the prosecution, to consult with their attorneys, and otherwise to participate in their defense. However, the Sixth Amendment permits courts to remove defendants who are disorderly, disrespectful, and abusive. If an unruly defendant insists on remaining in the courtroom, the Sixth Amendment authorizes courts to take appropriate measures to restrain him. In some instances, courts have shackled and gagged recalcitrant defendants in the presence of the jury. In other instances, defiant defendants have been removed from court and forced to watch the remainder of trial from a prison cell, through closed-circuit television.

Compulsory Process for Favorable Witnesses As a corollary to the right of confrontation, the Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to use the compulsory process of the judiciary to subpoena witnesses who could provide exculpatory testimony or who have other information that is favorable to the defense. The Sixth Amendment guarantees this right even if an indigent defendant cannot afford to pay the expenses that accompany the use of judicial resources to subpoena a witness (United States v. Webster, 750 F.2d 307 [5th Cir. 1984]). Courts may not take actions to undermine the testimony of a witness who has been subpoenaed by the defense. For example, a trial judge who discourages a witness from testifying by issuing unnecessarily stern warnings against perjury has violated the precepts of the Sixth Amendment.

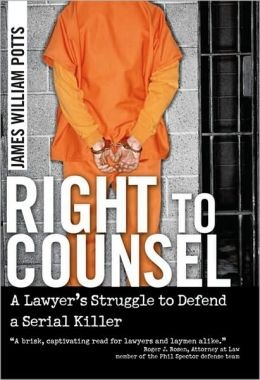

Right to Counsel Because of the law's complexity and the often substantial deprivations that a criminal conviction can produce, the Sixth Amendment provides criminal defendants with a Right to Counsel. A defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel attaches when the government initiates adversarial criminal proceedings, whether by way of formal charge, Preliminary Hearing, indictment, information, or Arraignment (United States v. Larkin, 978 F.2d 964 [7th Cir. 1992]). Unlike the right to a speedy trial, this Sixth Amendment right does not arise at the moment of arrest unless the government has already filed formal charges (Kirby v. Illinois, 406 U.S. 682, 92 S. Ct. 1877, 32 L. Ed. 2d 411 [1972]). However, defendants may assert a Fifth Amendment right to consult with an attorney during Custodial Interrogation by the police, even though no formal charges have been brought and no arrest has been made

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Grand juries, which return indictments in many criminal cases, are composed of a jury of peers and operate in closed deliberation proceedings; they are given specific instructions regarding the law by the judge. Many constitutional restrictions that apply in court or in other situations do not apply during grand jury proceedings. For example, the exclusionary rule does not apply to certain evidence presented to a grand jury; the exclusionary rule states that evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth, Fifth or Sixth amendments cannot be introduced in court. Also, an individual does not have the right to have an attorney present in the grand jury room during hearings. An individual would have such a right during questioning by the police while in custody, but an individual testifying before a grand jury is free to leave the grand jury room to consult with his or her attorney outside the room before returning to answer a question. The grand jury indictment clause of the Fifth Amendment has not been incorporated under the Fourteenth Amendment; in other words, it has not been ruled applicable to the states. States are free to abolish grand juries, and many (though not all) have replaced them with preliminary hearings.

The Bill of Rights in the National Archives.

Currently, fe

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

ike many other areas of American law, the Fourth Amendment finds its roots in English legal doctrine. Sir Edward Coke, in Semayne's case (1604), famously stated: "The house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well for his defence against injury and violence as for his repose." Semayne's Case acknowledged that the King did not have unbridled authority to intrude on his subjects' dwellings but recognized that government agents were permitted to conduct searches and seizures under certain conditions when their purpose was lawful and a warrant had been obtained.

The 1760s saw a growth in the intensity of litigation against state officers, who, using general warrants, conducted raids in search of materials relating to John Wilkes' publications attacking both government policies and the King himself. The most famous of these cases involved John Entick, whose home was forcibly entered by the King's Messenger Nathan Carrington, along with others, pursuant to a warrant issued by George Montagu-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax authorizing them “to make strict and diligent search for . . . the author, or one concerned in the writing of several weekly very seditious papers intitled, ‘The Monitor or British Freeholder, No 257, 357, 358, 360, 373, 376, 378, and 380,’″ and seized printed charts, pamphlets and other materials. In the resulting case, Entick v. Carrington (1765), Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden ruled that the search and seizure was unlawful as the warrant authorized the seizure of all of Entick's papers, not just the criminal ones and the warrant lacked probable cause to even justify the search. Entick established the English precedent that the executive is limited in intruding on private property by common law.

No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

In 1765, the British parliament enacted the first of the Quartering Acts, requiring the American colonies to pay the costs of British soldiers serving in the colonies, and requiring that if the local barracks provided insufficient space, that the colonists provide space for the troops to live in alehouses, inns, and livery stables. After the Boston Tea Party, the Quartering Act of 1774 was enacted; it was one of the Intolerable Acts that pushed the colonies toward revolution. The later Quartering Act authorized British troops to be quartered wherever necessary, including in private homes.

One of the few times a federal court was asked to invalidate a law or action on Third Amendment grounds was in Engblom v. Carey, 677 F.2d 957 (2d. Cir. 1982). In 1979, prison officials in New York organized a strike; they were evicted from their prison facility residences, which were reassigned to members of the National Guard who had temporarily taken their place as prison guards. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled: (1) that the term ownerin the Third Amendment includes tenants (paralleling similar cases regarding the Fourth Amendment, governing search and seizure), (2) National Guard troops count as soldiers for the purposes of the Third Amendment, and (3) that the Third Amendment is incorporated (that is, that it applies to the states) by virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The right to bear arms predates the Bill of Rights; the Second Amendment was based partially on the right to bear arms in English common-law, and was influenced by the English Bill of Rights of 1689. This right was described by Blackstone as an auxiliary right, supporting the natural rights of self-defense, resistance to oppression, and the civic duty to act in concert in defense of the state. Academic inquiry into the purpose, scope, and effect of the amendment has been controversial and subject to numerous interpretations. [

Controversy .  Aurora, Colorado.

On July 20, 2012, a mass shooting occurred inside of a Century movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, during a midnight screening of the film The Dark Knight Rises. A gunman, dressed in tactical clothing, set off tear gas grenades and shot into the audience with multiple firearms, killing 12 people and injuring 58 others. The sole suspect is James Eagan Holmes, who was arrested outside the cinema minutes later. James Eagan Holmes (born December 13, 1987) is the suspected perpetrator of a mass shooting

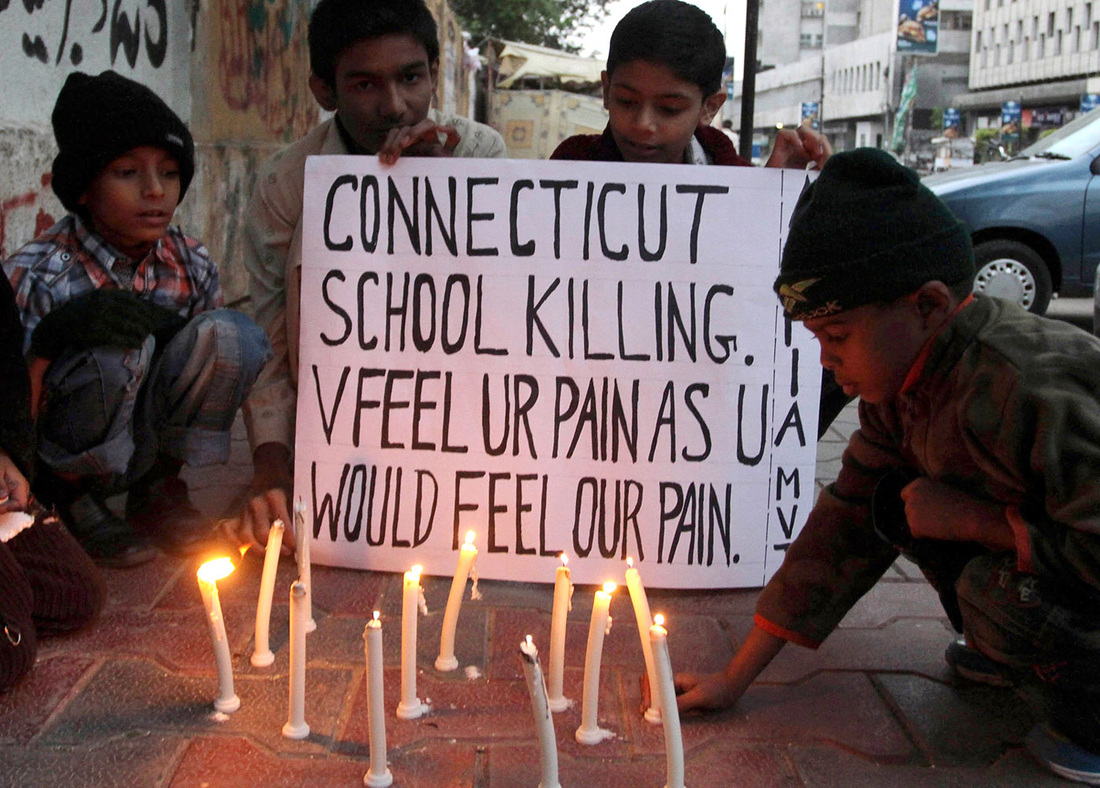

Sandy Hook Elementary School.

On December 14, 2012, Adam Lanza, 20, fatally shot twenty children and six adult staff members in a mass murder at Sandy Hook Elementary School in the village of Sandy Hook in Newtown, Connecticut. Before driving to the school, Lanza had shot and killed his mother Nancy at their Newtown home. As first responders arrived, he committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

The incident is the second deadliest mass shooting by a single person in American history, after the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre. It is the second deadliest mass murder at an American elementary school, after the 1927 Bath School bombings in Michigan.

The shootings prompted renewed debate about gun control in the United States, and a proposal for new legislation banning the sale and manufacture of certain types of semi-automaticfirearms and magazines with more than ten rounds of ammunition.

Virginia Tech massacare.

The Virginia Tech massacre was a school shooting that took place on April 16, 2007, on the campus of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg, Virginia, United States.Seung-Hui Cho, a senior at Virginia Tech, shot and killed 32 people and wounded 17 others in two separate attacks, approximately two hours apart, before committing suicide (another six people were injured escaping from classroom windows). The massacre is the deadliest shooting incident by a single gunman in U.S. history. It was the worst act of mass murder of college students since Syracuse University lost 35 students in the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, and the second-deadliest act of mass murder at a U.S. school campus, behind the Bath School disaster of 1927.

In his speech at the December 16 vigil, Obama called for using "whatever power this office holds", to prevent similar tragedies in the future. Within 15 hours of the incident, 100,000 Americans signed a petition at the Obama administration's We the People petitioning website in support of a renewed national debate on gun control. President Obama later affirmed that he would make gun control a "central issue" at the start of his second term of office, in a speech on December 19. On December 21, 2012, the National Rifle Association called on the United States Congress to appropriate funds for the hiring of armed police officers in every American school to protect students.

During the investigation into Adam Lanza's background, officials found that Lanza had possessed "thousands of dollars worth of violent video games". Though the link between Lanza's video game habits and the shooting was not yet clear from the investgators, the findings reopened debate on the hypothesized connection between violent video games and real-world crime.

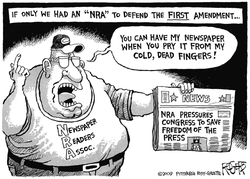

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering with the right to peaceably assemble or prohibiting the petitioning for a governmental redress of grievances. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that comprise the Bill of Rights. "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

Cases in which the amendment was used. Originally, the First Amendment applied only to the federal government, and some states continued official state religions after ratification. Massachusetts, for example, was officially Congregationalist until the 1830s.

In Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Supreme Court required states to meet the "strict scrutiny" standard when refusing to accommodate religiously motivated conduct. This meant that a government needed to have a "compelling interest" regarding such a refusal. The case involved Adele Sherbert, who was denied unemployment benefits by South Carolinabecause she refused to work on Saturdays, something forbidden by her Seventh-day Adventist faith. In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the Court ruled that a law that "unduly burdens the practice of religion" without a compelling interest, even though it might be "neutral on its face," would be unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court declined to rule on the constitutionality of any federal law regarding the Free Speech Clause until the 20th century. For example, the Supreme Court never ruled on the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, legislation by President John Adams' Federalist Party to ban seditious libel; three of the Supreme Court's justices presided over resulting sedition trials without indicating any reservations.

|